Marquette, Michigan, isn't exactly around the corner from Rochester, Michigan—an eight-hour drive, to be exact. Yet, for reasons that defy logic, I made the journey not once but twice. The first time, in 2022, I rode with Pat. The Marji Gesick 50 miler chewed us up and spat us out somewhere between exhaustion and self-loathing. We didn't finish. To officially drop out, Pat and I had to text #quitter to the folks holding our riding gear. If that wasn’t humiliating enough, our race results forever displayed #quitter next to our names. But in 2023, on my 58th birthday no less, I returned with Davin—his first Marji. Davin, an Army Reserve colonel, joined me, a Navy Submarine veteran, on a quest for redemption and a fresh batch of questionable decisions. Nothing was going to hold us back, for we had the end ingrained in our minds; I intended to finish what I started the year before, and I had Colonel Davin there to help me.

The Marji Gesick doesn’t just warn you it’s hard—it taunts you. Their slogans are like psychological warfare: "Finish What You Started" and "It Gets Worse Before It Gets Worse." First-timers are labeled "fresh meat," and in 2022, Pat and I were served up rare. But in 2023, I returned with a new partner, Davin. We were the proverbial grizzled meat, tougher but still uncertain if we could handle what lay ahead.

Section 1: Marquette to Jackson Mine Park (~20 Miles)

The race begins in downtown Marquette, where we were treated to a brief, scenic ride along Lake Superior. It’s serene, a cruel prelude to the chaos ahead. After crossing the main road, we hit Marquette Mountain Road, the first major climb. Stretching approximately two miles, it’s relentless, steep, and soul-crushing. By the time we crested the top, Davin and I quickly realized that pacing ourselves wasn’t just a strategy—it was survival.

From there, the course dove into dense woods and challenging singletrack. The first section ends at Jackson Mine Park near Negaunee, roughly 20 miles into the race. The mix of machine-built flow trails and hand-built challenges showcased the rugged creativity of the Noquemanon Trail Network (NTN), which has maintained these trails to provide some of the most challenging singletrack in the region. My Strava app later revealed we climbed about 1,500 feet of elevation in this section, but at that moment, all I could think about was putting one pedal stroke in front of the other.

As we reached Jackson Mine Park, it was clear that the Marji was not going to give us any freebies. The first 20 miles had already tested our endurance and forced us to adjust our pace, but deep down, I knew this was just the beginning of the battle.

Section 2: Jackson Park Loop (~25 Miles)

The second section, a 25-mile loop around Jackson Park, was as much a mental challenge as a physical one. Fatigue set in as we tackled root-riddled climbs and sketchy descents. Later in the section, the terrain took an even harsher turn as we approached a slick section of moss-covered rocks. Both Davin and I fell victim to the treacherous surface, each taking what we would later describe as 'atomic body slam' crashes. I hit the ground hard on my side, the shock momentarily leaving me stunned. "That was graceful," Davin groaned as he picked himself up, brushing dirt and moss off his jersey. "I think the ground broke my fall," I replied with a smirk, though my shoulder throbbed in protest. After a moment, Davin looked at me and shook his head. "Guess Todd is right—misery loves company," he said with a wry smile. We laughed, though it hurt to do so, and pressed on.

After dusting ourselves off and shaking away the pain, we pressed on. At a trail junction halfway into the loop, we encountered another moment of camaraderie. A man from Oregon, there to support his son, handed us PB&J sandwiches that tasted like the best meal we'd ever had. “Keep pushing,” he said, “you’re not as far behind as you think.” We chuckled.

As we rode on, we caught up with Mollie, a florist we’d met earlier. She was struggling on a particularly steep climb, but her sense of humor hadn’t wavered. "I don’t care if I make it to the finish," she joked, "as long as I can still feel my legs by morning." Her ability to laugh in the face of misery was contagious, and we carried that lightness with us through the rest of the loop.

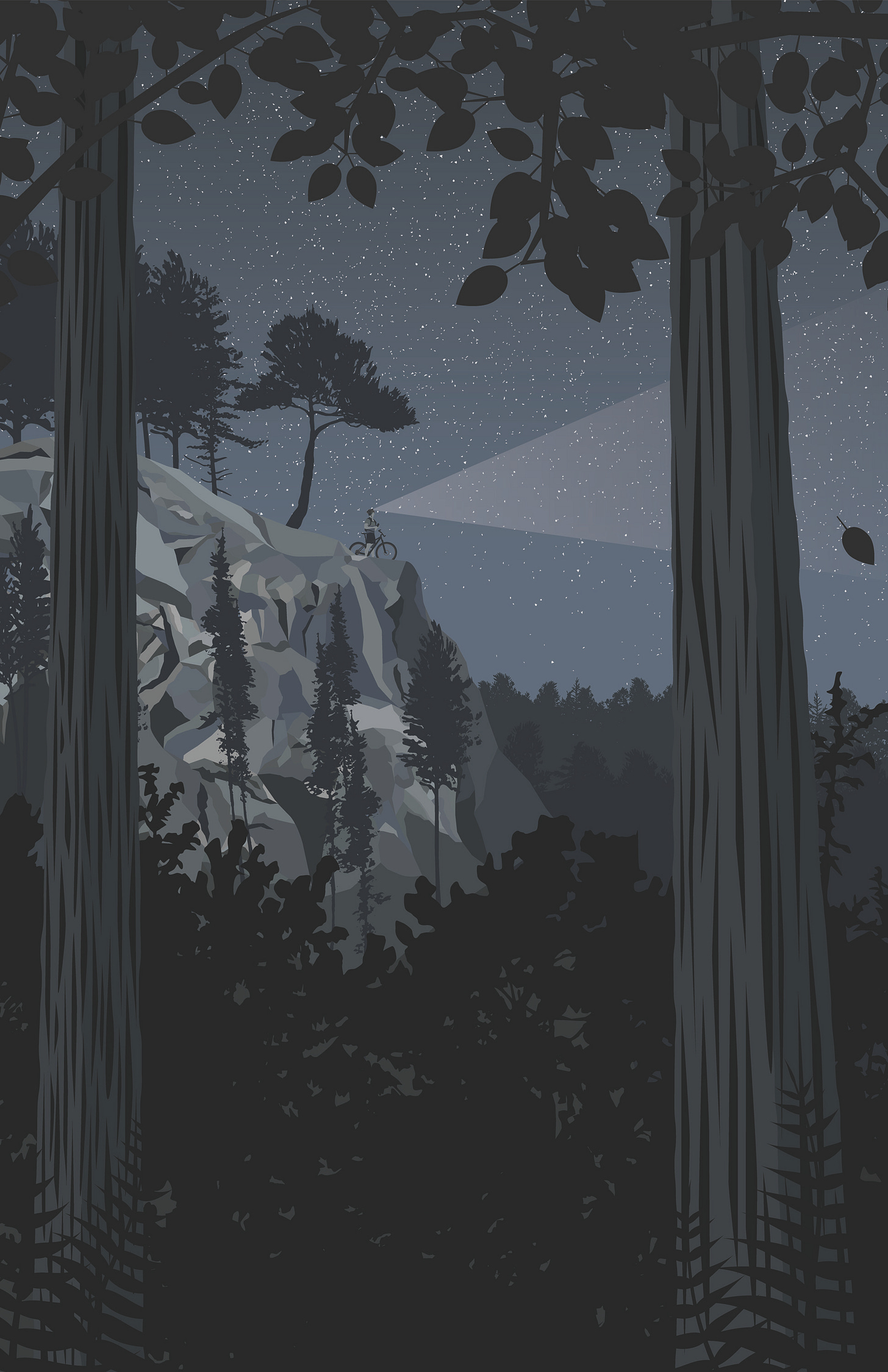

Despite these moments of levity, the second section remained punishing. The dense forest seemed to close in as the miles dragged on, and the constant technical challenges tested both our physical strength and our resolve. A narrow 8 inch trail section along a cliff tested our nerves. By the time we finished the second loop, our legs felt like lead, but our spirits were bolstered by the connections we’d made along the way.

Finishing the second loop felt like surviving a trial by fire. My body was already battered, and Davin’s resolve and patience with me was being tested with every mile. Yet, we pressed on, carried by the fleeting kindness of strangers and the camaraderie of those struggling alongside us.

Section 3: Final Leg (~18 Miles)

The final section, deceptively touted as "just" 18 miles, was the most brutal. Every climb felt steeper, every descent riskier. By this point, our bodies were spent, and even the smallest obstacles felt insurmountable.

We had this last leg to finish, but they would be the hardest 18 miles of our lives. At this point, the Marji had stripped us down to the bone. The terrain, the exhaustion, and the mental games had left us weathered, but there was a stubborn fire burning inside. All that stood between us and the finish line was the last stretch of our journey.

It was during this section, under the cover of darkness, that my headlamp met its demise. After my front tire snagged on a root, I was flung forward, landing hard and watching as my light snapped loose and tumbled into the dirt. "You okay?" Davin called back, his voice cutting through the night. "Yeah," I grumbled, dusting myself off, "but my light’s toast."

As if that weren’t enough, not long after, I misjudged a turn and plowed directly into a tree, snapping half of my rear brake lever clean off. The sharp crack echoed in the still night, and I could feel the sting of the latest insult to my bike and my body. "Well, there goes my stopping power," I muttered, trying to keep my frustration in check. Davin shook his head, "You’re falling apart one piece at a time, man. Let’s hope that’s the last of it."

The next few miles were a comedy of errors as I juggled holding the broken light in one hand while steering with the other—a circus act on two wheels. Just when my patience was about to snap, we encountered a trail angel stationed ahead. She had electrical tape at the ready. "Let me see that," she said, grabbing the broken light and taping it back onto my handlebars with the precision of a field medic. "Good as new—well, good enough to get you to the finish," she quipped. We laughed, the tension finally breaking as I tested her handiwork. It held.

Not long after, Davin found his own trouble—this time in the form of a Pabst Blue Ribbon. A different trail angel handed him the can, which he eagerly consumed in two long pulls. The cold beer hit him fast, lowering his body temperature and leaving him visibly shivering within minutes. "Damn, I think that was a mistake," Davin admitted through chattering teeth. It became clear he needed another layer to keep warm. I reached into my pack and pulled out a thin riding pullover that our friend Dave had insisted we carry. "Here," I said, handing it over. Davin slipped it on and immediately felt the warmth returning. "You seriously saved me with this," he said, gratitude written all over his face. "Remind me to thank Dave later."

As darkness fell deeper, Davin and I stumbled upon what can only be described as a surreal moment: a man in a full-body duck suit blasting Metallica while handing out snacks at an aid station. At first, we thought we were hallucinating. "Davin, do you see that?" I asked. "Please tell me I’m not losing it." He squinted, then laughed. "If you’re losing it, I am too." The heavy metal tunes confirmed it was, in fact, real. Moments like these, however bizarre, brought much-needed levity to an otherwise punishing experience.

The psychological games continued as we searched for the infamous Dum Dum lollipop tokens. The organizers had promised they would be spread throughout the course, but some checkpoints didn’t have any, leaving us questioning whether we had missed them entirely. To make things worse, the numbering of the stations was confusing—what seemed like checkpoint 2 was actually checkpoint 1, sending us into a spiral of doubt about whether we’d skipped a critical station.

Then came Nob Hill, an up-and-back climb that tested every ounce of strength we had left. A fake checkpoint midway up added to the confusion, tempting riders to turn around prematurely. But Davin and I chose to keep climbing, pushing through the steep, relentless ascent. When we finally reached the top, there it was—the final Dum Dum, perched like a trophy waiting to be claimed. We snatched it triumphantly, feeling a small but meaningful victory in an otherwise punishing section of the course.

By this point, the Marji had broken us down to the edge of ourselves. The punishing trails, the bone-deep fatigue, and the quiet wars in our heads had taken their toll, but a spark of defiance still burned inside. We weren’t empty yet — especially Davin. All that stood between us and the finish line were the last few miles – or was it five. What sick twist awaited us to blame Todd or Danny - the course designer?"

Crossing the Finish Line

We crossed the finish line at 1 a.m., after 17 grueling hours on the course. It was surreal. As we rolled to a stop, two race organizers approached us, their faces serious. "Dum Dums?" one asked, holding out their hand. My heart skipped a beat as I fumbled in my jersey pocket. Thankfully, I had all three—orange, brown, and white—but when Davin checked his own stash, his face turned pale. "Shit," he muttered, "I’ve got a duplicate." He looked like he was about to lose it.

Fortunately, I had anticipated some chaos and had grabbed extra Dum Dums along the way. I pulled out the third token he needed and handed it to him. "Here, don’t say I never gave you anything," I said with a smirk. Davin’s relief was palpable, and he muttered something about owing me a beer—probably several.

The organizers inspected our tokens carefully before handing over our rewards: four wooden tokens about the size of half-dollars—three for the checkpoints and a fourth for crossing the finish line. All of that—the blood, sweat, and literal tears—for four wooden tokens. We couldn’t help but laugh at the absurdity of it all.

That finish was more than a medal—it was proof that at 58 years old, stubbornness and grit still count for something.

Reflecting on the experience, the race director Todd’s famous quote comes to mind: "There is no finish line." The Marji Gesick isn’t just a race; it’s a test of resilience that stays with you long after you cross the line. It strips you down to your core, challenging not only your body but also your mind and spirit. Every mile, every crash, every absurd token search reminds you why you’re there—to prove to yourself that you can endure, that you can adapt, and that you can finish what you started.

As Davin and I shared a laugh—and maybe even a tear—I felt invincible. For 17 hours, we had lived in the moment, fighting the trail, the elements, and sometimes even ourselves. But in the end, it wasn’t just about conquering the Marji; it was about the journey, the camaraderie, and the realization that the hardest battles are often the ones worth fighting. And let’s be honest, we’ll probably be “Dum Dum” enough to sign up again. Davin did.